The Kaliwa Dam Project: The Social and Environmental Costs of Development in the Philippines

by Kimberly Navarro

The Philippine Context

The Philippines is a newly industrialized country that is home to numerous groups of Indigenous Peoples (IP), natural resources, and rich biodiversity. Its history is rife with tensions between government-sponsored development projects and IP groups fighting to protect access to their ancestral domains. The country has made great strides in economic development, but growth has come at the expense of the environment. The Philippines is dealing with decreasing forest cover, coastal degradation, and a growing list of vulnerable species. Despite the existence of legislation designed to protect IP groups and the environment, the government continues to use natural resources from these areas to meet the needs of the majority. Many of them are located in Metro Manila, the capital region of the nation consisting of numerous urbanized cities that experience high rates of income inequality. As resources dwindle and the population grows, the government is under pressure to keep pace with increasing demand for basic resources.

The Kaliwa Dam Project

Almost all of the water in Metro Manila comes from the Angat River (see Map 8), located north of the region. When the dam’s water level decreases, it leads to a water deficit which leaves tens of thousands of households in Manila without water (Sabillo, 2019). The government’s answer to the problem of water scarcity is the construction of the Kaliwa Dam, located west of Metro Manila (see Map 1). Construction is projected to be completed and operational in 2026 (Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System [MWSS], 2019; Raymundo, 2023). The dam will be 60 meters in height, with a 27.7 kilometer water conveyance tunnel extending from Tereza, Rizal to General Nakar, Quezon (see Map 1) that will move water from the Kaliwa River to Metro Manila’s water services areas (see Map 8) (MWSS, 2019). The dam project was part of former President Rodrigo Duterte’s “Build, Build, Build” Program, consisting of numerous infrastructure development projects meant to encourage economic growth, and its program is slated to continue under current President Bongbong Marcos’s “Build, Better, More” program (Patinio, 2022). These initiatives are funded through China’s foreign policy strategy of investing in infrastructure development projects in 125 countries (as of 2019) through the Belt and Road Initiative (World Bank, 2019).

Opposition to the Kaliwa Dam Project

Those critical of the project are numerous IP groups, local communities, environmentalists, church leaders, and conservationists concerned about the impact on ancestral domains, neighborhoods, protected areas, surrounding biodiversity, and geology. In July 2019, MWSS released a 370-page Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) conducted within a brief three month time frame. It discussed the project’s potential effect on the land, water, air, and people (MWSS, 2019). The EIS acknowledged the project’s potential impact on local flora and fauna biodiversity, and the concerns of affected communities, but was criticized by many to be largely descriptive, lacking technical analysis, using questionable methodology, failing to quantify the environmental impact, minimizing potential harm, and providing inadequate mitigation strategies (MWSS, 2019; Conde, 2019b). This paper seeks to evaluate the Kaliwa Dam’s potential impact on local communities and nearby biodiversity and explore alternative projects that do not threaten peoples’ livelihoods and the surrounding biodiversity.

The Dam’s Impact on IP and Local Communities’ Health and Way of Life

Based on participatory maps and existing literature, the environmental changes that would result from the dam threaten livelihoods, intensify disease, and displace communities. The EIS assessed that minimal communities would be affected, but advocacy maps reveal a minimum of five thousand IPs within the Agat, Dumagat, and Remontado tribes would be affected (see Map 2) (Conde, 2019a). These groups rely on the nearby forests for timber products, rattan, honey harvesting, fuelwood, fishing, farming, hunting, and local flora for food and medicine (Moussavi & Navarra, 2021). When the nearby Laiban Dam (see Map 1) was being constructed, local people were banned from using the land which led to increased rates of food insecurity (Conde, 2019b). Communities within and nearby the project area also depend on local springs as a source of potable water and the dam’s construction and operation threaten open access to these resources which increase the risk of diarrhea, malnutrition, and stunting. Rural barangays (villages) already experience worse health outcomes compared to their urban counterparts due to a combination of factors such as poor health system governance in rural areas, and limited access to financial capital. The creation of a dam could further exacerbate these health inequities to the detriment of the IP groups and farming households. Additionally, affected communities are at risk of being exposed to diseases associated with dams. For instance, the worldwide increase of the parasitic flatworm causing schistosomiasis has been directly connected to dams because they prevent the migration of freshwater prawns that eat the snails hosting the disease (Sokolow et al., 2017). The Philippine Department of Health (n.d.) reports that schistosomiasis is endemic to the country and that about 2.5 million people are directly exposed to it. To make matters worse, potential flooding could displace 84,000 residents in the Infanta municipality east of the project area (Conde, 2019a). Other communities along the Kaliwa River could also become isolated and require longer bridges for their commute (Conde, 2019a). Displacement of these communities have profound implications for nearby communities since they can see an increase in migration, further straining limited resources in rural areas.

Earthquake Risks

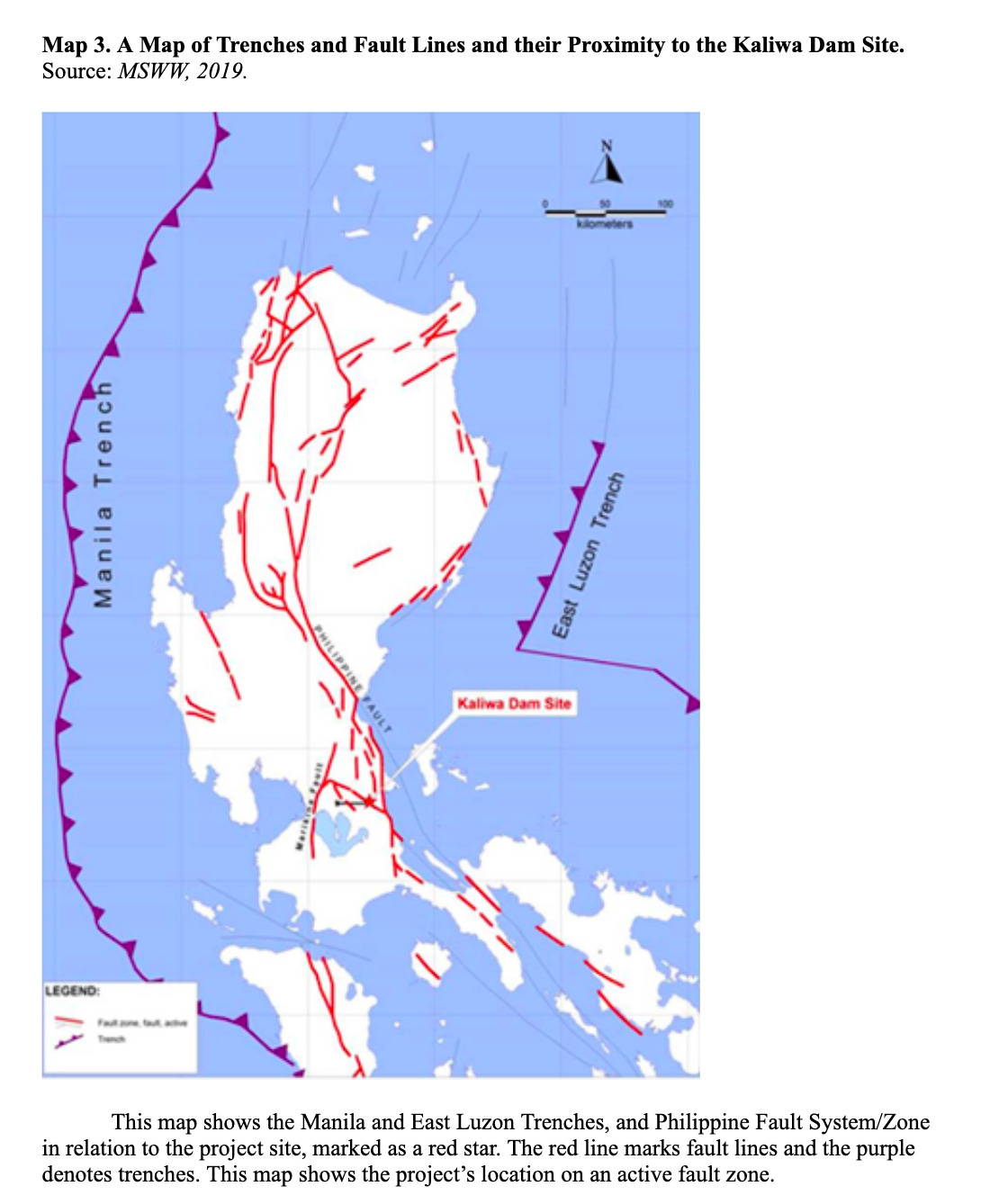

The project’s location on fault lines is also a cause for concern for many affected communities. The EIS acknowledges that the dam is being built on the Philippine Fault Zone, but states that there are no active faults near the dam, with the closest one situated 15 kilometers east in Infanta (see Map 3) (MWSS, 2019). However, literature shows that large dams can trigger earthquakes, a phenomena called Reservoir-Induced Seismicity (RIS). Extra water pressure in cracks beneath and near a reservoir can lead to movements in the fault line causing tremors (Kornijów, 2009; Tosun, 2015; Stratbase ADR Institute, 2021). Between 1935 and 1984, thirty-two reported cases of large dams caused earthquakes greater than a 4.0 magnitude in the Richter scale globally (McCully, 1996). Although many of these dams were over 100 meters in height, a few were around 60 meters, similar to the Kaliwa Dam’s planned height (McCully, 1996; Kornijów, 2009). For most studied RIS cases, seismic activity increased within 25 kilometers of the reservoir (McCully, 1996; Kornijów, 2009). Assuming the MWSS report is accurate, this means that the Kaliwa Dam’s 15 kilometer proximity to an active fault line could intensify seismic activity. Although there is no guarantee that an earthquake will happen, as RIS patterns are unique for every reservoir, it is an added risk that was not adequately addressed by the EIS. Should an earthquake occur, it could lead to extensive damages at the dam site and the conveyance tunnel, affecting areas around it. Should the dam break, flooding could destroy habitats, displace communities, and cause numerous fatalities.

Existing Biodiversity in the Project Area

The Sierra Madre mountain range is home to already threatened and vulnerable species that would be impacted by the dam. According to the Philippine conservation group, Haribon Foundation (2018), Presidential Proclamation No. 1636 protects parts of the Sierra Madres forests and coastlines, which is a key habitat to 15 amphibian species, 334 bird species, 1476 fish species, 963 invertebrate species, 81 mammal species, and 60 reptile species. The Foundation (2018) further explain that the Kaliwa Watershed of approximately 12,000 hectares of forests has a recorded 39 endemic plant species, 17 of which are threatened or vulnerable to endangerment (see Map 6 and Map 7). The dam and conveyance tunnel will be located on this watershed, and a National Park and Wildlife Sanctuary (NPWSG) (see Map 5). The watershed in particular is home to threatened wildlife such as the Philippine Hawk-Eagle (Nisaetus philippensis), the Brown Deer (Rusa Marianna), the Warty Pig (Sus philippensis), the Northern Rufous Hornbill (Buceros hydrocorax), and the Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi), in addition to the birds found in the Luzon Endemic Bird Area (Haribon Foundation, 2018). The construction and operations of the Kaliwa Dam have wide-reaching implications on the survival of the wildlife that live here and the surrounding ecosystem that depend on their presence.

The Dam’s Impact on Biodiversity

The EIS claims that the dam’s environmental impact is minimal, but opposition groups are deeply concerned about its potential to cause irreversible environmental damage to the Sierra Madres mountains, particularly the southern region where the dam is being built (see Map 4). Further review of a World Bank report assessing the impact of large dams in these areas reveal that opposition groups have a right to be concerned. In 2012, the World Bank concluded that dams over 15 meters tall could permanently cause flooding in these areas which would be detrimental to the local biodiversity and require an “elaborate and compensatory” management plan. This contradicts the EIS’s statement that the 60 meter tall dam will cause minimal harm to the surrounding areas. One specific impact that large dams have on the environment is that it causes habitat fragmentation, and blocks the flow of the river water from upstream to downstream areas. According to the World Bank (2012) report, the dam would prevent the migration of fish, affecting reproductive patterns and the surrounding ecosystem that depend on them. Literature shows that species diversity decreases due to flooding commonly attributed to dams in tropical rivers (Benchimol, 2015). Large areas of forests turn into shallow bodies of water with small islands, resulting in insular biotas and accelerating extinction rates over time (Benchimol, 2015). Moreover, fewer large trees and decreased canopy coverage would result in higher temperatures and possibly a decrease in humidity, which may be hostile to the amphibians and reptiles because their reproductive patterns are largely dependent upon the environment (Diesmos, 2007). Deforestation would also have a negative impact on regulating extreme weather and the forest’s role as a carbon sink. The United States Agency for International Development (2016) states that the forests in these watersheds play a critical role in regulating water flow towards Metro Manila and mitigating flooding during typhoons. Inundation and decreased canopy coverage threaten the key habitats home to aforementioned species, many of which are vulnerable and endemic to the Philippines.

Alternative Projects with Fewer Threats to Biodiversity

The World Bank and Haribon Foundation identified other options that could improve water security in Metro Manila without threatening the biodiversity and livelihoods of local communities. Although the World Bank (2012) report favored the use of freshwater sources, it also identified water desalination and rainwater harvesting as other options. Water desalination is an extremely resource-intensive option that could have negative impacts on the environment so it’s unlikely to be a feasible or sustainable option, but rainwater harvesting is an underutilized choice that could provide water to many homes in Metro Manila. The Rainwater Collector and Springs Development Act of 1989 is a law requiring all barangays to create rainwater harvesting systems in the nation but hasn’t been implemented (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2019). It is a cost-effective and sustainable option that can prevent flooding and provide water during dry seasons (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2019). Additionally, the Haribon Foundation (2018) proposed the restoration and conservation of existing water reservoirs and watershed forest reserves, like the Angat Watershed where Metro Manila gets most of its water from. The Foundation (2018) also stated that more economical options include improving water distribution systems and facilities to reduce leakages in water pipes, and recycling used wastewater for agricultural irrigation and industrial uses. These are promising alternatives that could provide water for Metro Manila while decreasing the threat to local communities and biodiversity.

Conclusion

Based on existing literature, infrastructure development projects in the Sierra Madre area have adverse social and environmental effects on the surrounding areas. The proposed location of the Kaliwa Dam is on a fault zone which poses a risk to earthquakes, dam failure, and flooding, threatening the livelihoods of local communities. Moreover, the project could trigger the migration or extinction of local wildlife, including endemic species and species under conservation status. The EIS publication did not provide an accurate picture of potential risks associated with the dam site and tunnel construction, nor did it include adequate mitigation strategies for affected areas. Instead, it was used more of a bureaucratic stepping stone to begin construction that did not consider alternative options. The disregard for protected areas, lack of transparency and questionable acquisition of project certification imply poor governance, by which government agencies bypass legal instruments meant to involve and acquire consent of local stakeholders.