The Impact of China's Belt and Road Initiative on Zambia: History of Development Aid from China to Africa

By Felix Akoyam

History of Development Aid from China to Africa

China began cultivating relationships with most African countries in the 1960s when many nations on the continent started gaining independence from colonial powers. Beijing has conventionally presented itself as the largest developing country, partnering with other developing nations for their mutual interest, not as a donor. Perhaps the most significant event that laid the foundation for the current China-Africa relations is the November 2006 China-Africa summit that was held in Beijing, King (2007). An overwhelming number of African states, 48, were at this high-level conference. The Chinese government pledged its unflinching development assistance to African countries by increasing its support to countries by 100 percent in 2009, offering $3 billion in preferential loans and another $2 billion in special export buyer’s credit on better terms and more importantly offered debt relief to Highly Indebted Poor and less developed countries on the continent, China Foreign Affairs Ministry (2006).

Despite all these significant investments and China’s deliberate attempt to project itself as a peer which has the interest of these countries at heart, it does not appear to have a favorable image among all the countries on the continent. The Center for Democratic Development’s Afro barometer survey in 2016 revealed that Tunisia, Ghana, and Madagascar had a negative view of China’s investments on the African continent (Breuer, 2017).

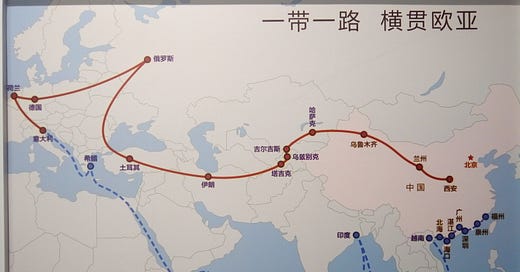

China introduced the One Belt, One Road initiative (OBOR) in 2013, to build an infrastructure network coupled with an economic belt from China, transcending Central Asia to Europe to Africa. The OBOR initiative is equally aimed at building mutually beneficial relations among countries in trade, technology, environmental sustainability, and counterterrorism.

Avid critics of the Belt and Road initiative have argued it is a grand scheme to only further the interest of Beijing. Breuer (2017), contends that Zambia, Djibouti, Egypt, Tanzania, and Ethiopia which have been described as hotspots of Belt and Road countries in Africa, are of strategic essence to China’s Maritime Silk Road due to their physical location. China is not only making significant investments in ports, roads, railways, East Africa and Southern Africa, but also West Africa, which costs are borne by the respective countries, but Beijing stands to benefit from these projects the most in the long run. For instance, China Merchants Holding International has not only funded the construction of Djibouti’s Doraleh port but ports in Togo, Nigeria, all in West Africa. Linking ports from coast to coast within the continent provides China an opportunity to conveniently transport most of its raw materials, and most significantly, as argued again by Breuer (2017), Africa serves as a huge export market for China as it is increasingly taking over the production of several goods that were traditionally produced on the continent.

The Zambian Experience with Belt & Road Initiative

Zambia began a massive infrastructural drive in 2014 that saw the country put up nearly 20 huge infrastructure projects mainly financed by Beijing through a bilateral agreement through the Belt & Road Initiative at a cost of about $9 billion. All these projects including the expansion of the country’s biggest airport, the construction of a new airport, and the building of new stadia were constructed by Chinese companies with Chinese experts, while the menial jobs were left to locals. In effect, though Zambians are going to spend years paying for the projects, a huge part of the money for the project that could have stayed in the hands of qualified Zambian professionals was sent back to China.

That notwithstanding, some of the projects which have spiraled Zambia’s debt to China have been described as “White Elephant Projects”. For instance, the Chinese through its Belt and Road Initiative constructed a 40,000-seater stadium for $65 million. The stadium reportedly barely attracts more than 5,000 spectators (Orr, 2020). Zambia’s current debt to Chinese entities stands at about $3 billion which the country is struggling to pay. The Southern African country has tried to renegotiate to refinance its ballooning debt to China. But this move has been met with fierce resistance from China.

Some economists have predicted that Chinese firms intend to liquidate many assets including Zambia’s huge copper mine. China’s growing influence in Zambia has surpassed infrastructure or taking control of the country’s natural resources. The Chinese media conglomerate, Star Times, now holds a 60 percent stake in Zambia’s state broadcaster, ZNBC. There are heightened concerns that China will take over the country’s electricity company and its biggest airport in the capital, Lusaka, with Zambia struggling to meet its debt obligations to China (Anoba, 2018).

Ceelo and Nakamba-Kabaso (2018), argue there has been a longstanding uneasiness about China-Zambia relations since the Belt and Road Initiative commenced in the Southern African nation. Rumors of Zambian state-owned companies’ takeovers, private lands, and growth of “China town”, as well as Chinese nationals taking over menial jobs have become some of the most popular anecdotes even for the common Zambian man on the streets. Most significantly, traditional jobs like small food vending businesses locally known as “Nsima”, small poultry farms, and retail trading were jobs reserved mostly for unskilled Zambians in the informal sector are increasingly being taken over by Chinese nationals.

Consequently, there is growing resistance to Chinese investments in Zambia now. Looting of Chinese-owned shops and official protests have become symbolic tools of opposition to the Belt and Road Initiative in Zambia. An opposition leader called James Lukuku hit the streets in September 2018, to protest Chinese investments, which he described as ostentatious and needless. His party’s slogan “Say No to China” has reportedly gained traction among many young Zambians and on Twitter trends anytime the Chinese government or investors inaugurate new projects in Zambia. Beyond the usefulness of Chinese investments, many Zambians continue to question the transparency of loans contracted by Zambia from China, with many holding the view that Chinese loans have become an avenue for grand corruption in the country (Abu-Bakarr & Fang, 2019).

Zambia is not the only African country that finds itself in this quagmire, with some economic watchers on the continent holding the view that China is deliberately trapping these countries with unsustainable debt for exploitation of their natural resources, which Beijing needs to keep its industries running. For instance, more than 70 percent of Kenya’s $50 billion debt is owed to China, Africa’s most populous nation Nigeria, recently took $5 billion from China, with its ‘anglophone neighbor’, Ghana, considering mortgaging a protected forest reserve to China to mine bauxite in return for a $4 billion facility for infrastructure projects (Anoba, 2018).

In the West African nation of Sierra Leone, China through its Belt and Road program has agreed to offer the country $55 million to construct a fishing harbor that will cover an area of about 100 hectares. Details of this project sparked concerns after it emerged that the project could destroy a nearby rainforest and Sierra Leone's budding tourism sector (Johnson, 2021). Globally, and within West Africa, China is building ports and acquiring fleets to help meet its fish demand.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Balding (2018), contends China faces an uproar both at home and abroad due to the outcomes of the Belt and Road Initiative. Some Chinese individuals are unhappy about what they perceive to be wasteful spending on other countries, while many Belt and Road countries are responding with resentment which is impacting elections in such countries. Malaysia’s 2018 elections provide a classical instance where former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohammed, who widely campaigned against Chinese influence, defeated the incumbent, Najib Razak who had facilitated several Belt and Road projects tainted with corruption. Back in Africa, a government clampdown on graft related to Belt and Road projects led to the incarceration of several officials who were accused of corruption in Kenya while a Zambian policy thinktank cautioned against the lack of transparency regarding terms of loans contracted by Zambia under the Belt and Road initiative (Balding, 2018).

Moreover, developing countries must resist being cajoled into borrowing to unsustainable debt levels in the name of infrastructure development as we have seen in Zambia. They must uphold fiscal discipline and only prioritize borrowing for infrastructure projects that are needed to provide basic essential services for their people. Again, countries must prioritize environmental sustainability in their quest for development for their respective countries.

Despite China’s constant claim of a win-win beneficial relationship with its Belt and Road project, Beijing appears to be the bigger beneficiary, especially in African countries like Zambia. Zambia and others in the sub-region must reduce corruption, and prioritize spending on needed infrastructure while encouraging private sector growth to ease the burden and its appetite of running to other Bretton Woods institutions or China for assistance.

References

Abu-Bakarr, J. Fang W. ( 2019). Resistance Growing to Chinese presence in Zambia. Retrieved on September 6, 2021, from https://www.dw.com/en/resistance-growing-to-chinese-presence-in-zambia/a-47275927

Anoba, I. (2018). China is taking over Zambia’s National Assets, but the Nightmare is just getting Started for Africa. Retrieved on September 28, 2021from https://www.africanliberty.org/2018/09/10/china-is-taking-over-zambia-national-assets-but-the-nightmare-is-just-starting-for-africa/

Balding, C. (2018). Why Democracies are turning against Belt and Road. Retrieved from https://alinstitute.org/images/Library/DemocraciesTurningAgainstBeltandRoad.pdf on September 25, 2021.

Breur, J. (2017). Two Belts, One Road? Stiftung Asienhaus. 10.11588/xarep.00004092

Cai P. (2017). Understanding China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Retrieved on October 6, 2021 from https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/understanding-belt-and-road-initiative

China, Foreign Affairs Ministry. (2004). Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Beijing Action Plan (2007-2009). Retrieved from https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/zflt/eng/zyzl/hywj/t280369.htm on September 20, 2021.

Johnson, B. (2018). The Belt and Road Initiative: Hook, Line and sinker? The Economist.

Lisinge, R. (2020). The Belt and Road Initiative and Africa’s regional infrastructure development: implications and lessons, Transnational Corporations Review, 12:4, 425-438, DOI: 10.1080/19186444.2020.1795527

Orr W. (2020) The Curse of White Elephant: The Pitfalls of Zambia’s Dependence on China. Retrieved on February 28, 2021from fhttps://globalriskinsights.com/2020/12/the-curse-of-the-white-elephant-the-pitfalls-of-zambias-dependence-on-china/

Smith, E. (2020) Zambia’s Spiraling Debt offers a glimpse into the future of Chinese loan financing in Africa. Retrieved on February 28, 2021from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/01/14/zambias-spiraling-debt-and-the-future-of-chinese-loan-financing-in-africa.html

Venkateswaran L. (2020). China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Implications for Africa. Retrieved on February 28, 2021 from https://www.orfonline.org/research/chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-implications-in-africa/