Reimagining Ethnic Minority Marginalization through Identity, Gender, and Land

By Mst. Sabikun Naher

Introduction and Background

The marginalization of ethnic minorities is a deeply rooted issue that intersects with various aspects of society, including identity, gender, and land use. This article aims to explore these intersections to provide a comprehensive understanding of the challenges faced by marginalized communities. Colonial and post-colonial policies have often disrupted indigenous ways of life, leading to socio-economic and cultural marginalization. By examining identity formation, gender dynamics, and land use through the politics of knowledge, the article seeks to highlight how these elements contribute to the marginalization of ethnic minorities. The article draws on the politics of knowledge and coloniality, as well as the anthropology of the state, to understand how colonial and post-colonial states construct ethnic territories through the production of knowledge and “colonized subjects” to extend control over space, population, and nature (Anthias & Hoffmann, 2021). The politics of knowledge (POK) play a crucial role in shaping identity formation, gender dynamics, and land use in the context of ethnic marginalization. These dynamics often reflect the interests of those in power, raising questions about who holds power and for whose benefit. POK challenges the dominant narratives shaped by colonial and post-colonial periods and highlights the importance of indigenous knowledge systems. These systems, which emphasize sustainable practices and deep ecological understanding, are frequently excluded in favor of national interests without considering local and contextual knowledge. Through a critical discourse analysis of theoretical contributions to POK, this article examines the intricate dynamics of identity, gender, and land use that collectively marginalize indigenous communities over time.

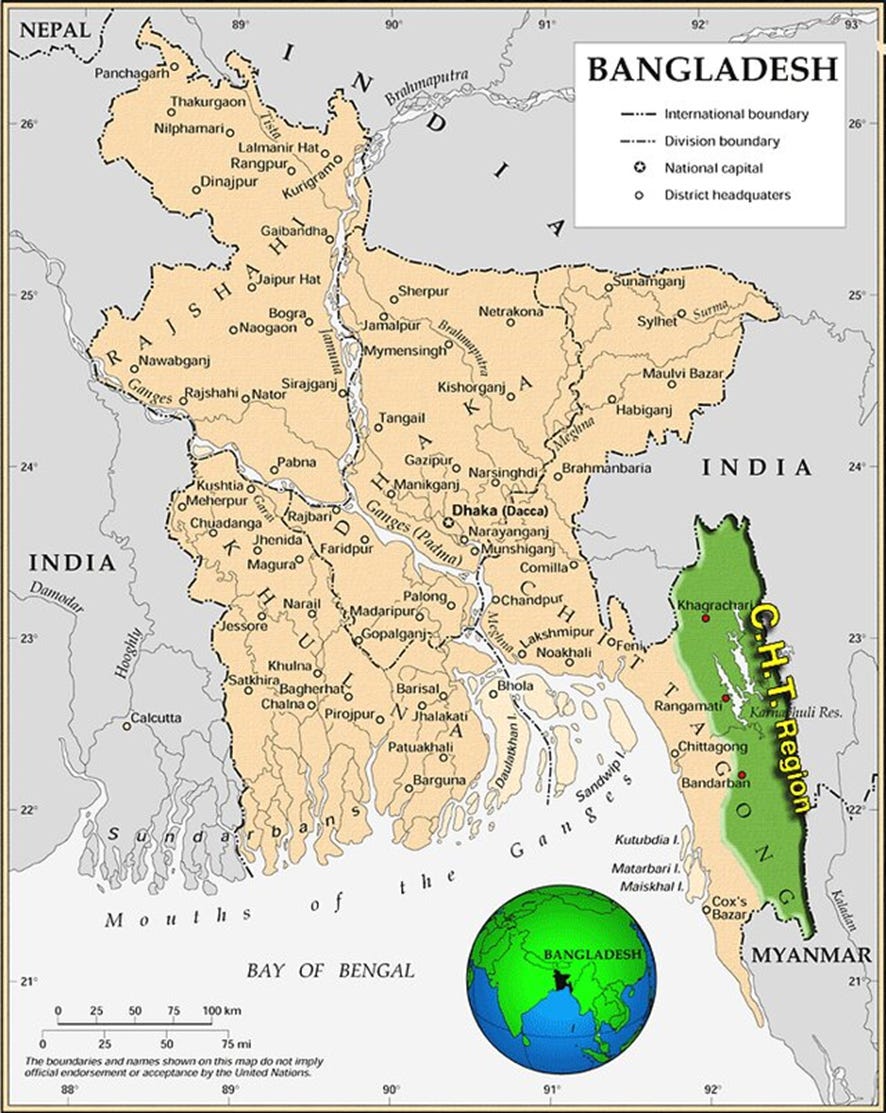

Using the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) of Bangladesh as a case study, the research examines the contemporary dynamics of marginalization and how they have been shaped by these longer histories, with a focus on identity, gender, and land use. The CHT region, home to diverse indigenous communities, has seen ongoing conflicts related to identity formation, gender dynamics and land rights. The article also explores how environmental discourses by dominant ethnic groups and the state have constructed CHT as “other,” shaping the dynamics of state-building and majority-minority relations over time. The hegemony of colonial British (1871–1947), post-colonial Pakistani (1947–1971), and Bangladeshi (1971–present) rule in CHT has had devastating impacts through the alienation of ethnic minorities from land and natural resources in the name of conservation and development. This has led to political and economic marginalization through narrowly defined citizenship and antagonistic relations with colonial and post-colonial regimes (Mohsin, 1997, 2003; Roy, 2000).

Theoretical Contributions of Politics of Knowledge (POK)

Early theoretical contributions of POK

The politics of knowledge (POK) is a multifaceted field with contributions from various scholars who have explored how power dynamics influence the production, dissemination, and validation of knowledge. They have significantly shaped our understanding of how knowledge is intertwined with power, influencing debates on equity, justice, and inclusiveness in knowledge production. The application of indigenous knowledge systems is not exceptional with this practice.

Michel Foucault (1980) explores the relationship between power and knowledge, arguing that they are not separate entities but deeply connected. He theorizes that power and knowledge directly influence each other where power creates knowledge, and knowledge reinforces power. This relationship is apparent in how societal norms and truths are established (Foucault, 1980). In 2006, Foucault delved deeper into the practical application of power through examining governing systems and societal mechanisms. Foucault explores how modern states apply control over their populations through a combination of governing techniques and rationality by defining governmentality as the 'conduct of conduct,' which refers to how the behavior of individuals or groups is directed (Foucault, 2006). Similarly, Edward Said explains how knowledge about the Orient is constructed and used by the West to exert control. This relationship between power and knowledge is central to the concept of Orientalism by examining how cultural representations of the East are deeply intertwined with political and economic interests. Said’s Orientalism challenges readers to critically examine how cultural narratives are constructed and the implications these narratives have on global power dynamics. Said explored how Western knowledge about the East was constructed through colonial power, reinforcing stereotypes and justifying imperial domination (Said, 1978).

Sandra Harding’s standpoint theory emphasizes the importance of marginalized perspectives, particularly those of women and oppressed groups, in producing more objective understandings of social reality (Harding, 1991). Haraway’s concept of ‘situated knowledge’ critiques the idea of objective, detached knowledge, arguing that all knowledge is produced from specific social and historical contexts (Haraway, 1988). Latour’s actor-network theory (ANT) delves into how scientific facts are constructed through intricate networks of human and non-human actors, challenging the traditional notion of science as purely objective (Latour, 1987). Santos’s Epistemologies of the South recognizes and validates the knowledge systems of marginalized communities, advocating for a more inclusive approach to knowledge production (Santos, 2014). Tuana’s exploration of epistemic injustice highlights how ignorance and knowledge are unequally distributed across social groups, often to the detriment of marginalized populations. Jasanoff’s research in science and technology studies (STS) examines the co-production of science and social order, revealing how scientific knowledge and societal norms are mutually constitutive (Jasanoff, 2004). Spivak’s ‘subaltern studies’ focus on amplifying the voices and knowledge of those marginalized by colonial and post-colonial power structures, critiquing the dominance of Western epistemologies (Spivak, 1988). Smith’s work on decolonizing methodologies emphasizes the importance of indigenous knowledge systems and critiques the ways in which Western research practices have historically marginalized indigenous peoples (Tuana, 2006).

Emerging theoretical contributions of POK

The politics of knowledge is a dynamic and evolving field, with current debates and emerging theories addressing various aspects of how knowledge is produced, validated, and utilized within political contexts. It has added new dimensions with knowledge over time. One prominent debate, as explored by Moore et al. (2020), centers around the tension between technocratic and populist approaches to governance. Technocracy emphasizes the role of experts and evidence-based policy-making, often at the expense of democratic engagement. In contrast, populism prioritizes the will of the people, sometimes disregarding expert knowledge. This dichotomy raises critical questions about the legitimacy and accountability of knowledge in democratic societies.

Adding to this discourse, Hunt et al. (2022) introduce the concept of epistemic injustice, which refers to the ways in which certain groups are marginalized in the production and validation of knowledge. This includes both testimonial injustices, where individuals are discredited due to prejudice, and hermeneutical injustice, where a lack of shared understanding prevents certain experiences from being adequately communicated. Addressing epistemic injustice involves recognizing and valuing diverse forms of knowledge, thereby promoting a more inclusive epistemic landscape. Jasanoff’s work focuses on the movement to decolonize knowledge, which seeks to challenge and dismantle the colonial legacies embedded in academic and scientific practices. This involves questioning the dominance of Western epistemologies and promoting indigenous and other marginalized ways of knowing. Decolonizing knowledge aims to create more inclusive and equitable systems of knowledge production, ensuring that diverse perspectives are acknowledged and respected. The spread of disinformation and misinformation has become a critical issue in contemporary politics, as highlighted by various scholars. This involves the deliberate dissemination of false information to manipulate public opinion and undermine trust in institutions. Addressing this challenge requires enhancing media literacy, promoting responsible journalism, and developing strategies to counteract false narratives (theoryofknowledge.net, 2024). Democratic epistemology, as discussed by Moore et al. (2020), explores how democratic principles can be applied to the production and validation of knowledge. This involves fostering open, inclusive, and participatory processes that allow diverse voices to contribute to knowledge creation. It also emphasizes the importance of transparency and accountability in scientific and academic practices. Intersectionality, as examined by Hunt (2022), looks at how various forms of social stratification, such as race, gender, and class, intersect to influence the production and validation of knowledge. This perspective highlights the need to consider multiple dimensions of identity and power in understanding how knowledge is constructed and whose knowledge is valued.

Navigating Identity, Gender, and Land Use in Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT)

Historical background in CHT

The Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) of Bangladesh is the country’s only mountainous area, with 43 percent of the total country's forest, 10 percent of the country's territory, about 10 million forest-dependent people, and home to at least 12 tribal communities (Ahammad & Stacey, 2016; Rasul, 2007)(See Annex 1: Map of CHT). The British employed a variety of initiatives and strategies to promote robust administration and development, which have developed tensions among the indigenous people due to changing their land rights and socio-economic diversity (Golam, 2005). During the post-colonial Pakistan regime, more hardships occurred for the indigenous population's way of life. Once the Pakistani government came to power and enacted many development plans, the struggle between the government and the indigenous people of CHT intensified. Because of the 1962 construction of the Kaptai Hydro-Electric Dam near Chittagong, which rendered thousands of hill people homeless and landless, the indigenous people were forced to flee to India and Myanmar (Ashrafuzzaman, 2014), and led to internal displacement (Mohsin, 1997).

The primary goal of the development plans in the CHT was economic development rather than cultural development. Indigenous values, customs, and means of subsistence were ignored. The rights to their ancestral land were curtailed by several development laws and schemes. The Peace Accord of 1997 was signed by the government and the people of the CHT following protracted political negotiations and the creation of the state of Bangladesh. The Peace Accord sought to establish a political framework for resolving CHT's insurgency (Ashrafuzzaman, 2014; Mohsin, 1997). Numerous issues, including resource usage, land, and forest ownership, conflict resolution with non-Bengali migrants, and other sociocultural, political, and religious variables have made life worse for indigenous peoples as a result of the peace process (Iqthyer, 2013). However, when the government did not carry out the Peace Accord as intended, tensions between the Bengali settlers and the native population intensified (Mohsin, 1997, 2003). The outcome of the state’s intervention is the marginalization of CHT people.

Navigating identity in CHT

The Chittagong Hill Tract (CHT) people have faced marginalization through various processes. A significant factor in this marginalization is the identity formation imposed by colonial and post-colonial rulers. The state has labeled the CHT people as "Pahari" (people who live in the hills) and "Upajati" (sub-nation), which has further marginalized them in social, economic, and political contexts (Uddin, 2012). Additionally, marginalization in the CHT has resulted from practices such as ethnocide (Chakma, 2010), genocide (Levene, 1999), eviction from ancestral lands (Rozaria, 2016; Rahman, 2011), and the state's development activities (Rahman, 2011). Identity construction is a dynamic and contextual process that involves connecting with a group and being identified by others (Duveen, 2001). However, this process is also shaped by power dynamics. Colonial powers have often constructed derogatory identities for the colonized, labeling them as savages, uncivilized, lazy, irrational, uneducated, untrustworthy, unreliable, and unpredictable (Ghosh et al., 2008). These colonial constructions serve the interests of the colonizers by dehumanizing those under colonial rule, thus legitimizing their subjugation (Reddy & Gleibs, 2019). Two primary interests guide the identity construction by colonial powers, which persist in the CHT over time: justifying conquest and exploitation and instilling a sense of self-unworthiness in the native people to ensure their complicity in their own marginalization (Ghosh et al., 2008). Furthermore, ethnic identity construction contains a territorial aspect. Research indicates that the establishment of ethnic territories is closely linked to the processes of land dispossession experienced by ethnic minorities (Bhandar, 2018) and that these experiences can vary significantly within minority groups based on factors like class or gender (Giovarelli & Wamalwa, 2011).

Navigating gender dynamics in CHT

Marginalization in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) has severely impacted the local population, particularly women. This situation has created extremely vulnerable conditions, raising serious safety and security concerns for indigenous women and girls. They are at risk of forced disappearances, physical and sexual violence, rape, torture, and forced marriage (D’Costa, 2014). Although the Peace Accord of 1997 was signed to address these issues affecting women, the accord itself is gendered and lacks explicit guarantees to address violence against women (Guhathakurta, 2012). Additionally, no specific networks have been developed in the CHT to protest violence against women (D’Costa, 2014). Feminist Political Ecology (FPE) offers a valuable framework for understanding the gendered aspects of land access, rights, dispossession, knowledge production, and discourse, as well as the ontology and epistemology involved in shaping women's environmental subjectivity. FPE emphasizes politics and power at various levels, highlighting gendered power relations and making a clear commitment to addressing gender disadvantage and inequality (Elmhirst, 2015, p. 519). Special attention is given to how gender and other power dynamics between men and women, or among women themselves, intersect to shape access to and control over resources or property in specific contexts (Sato, 2019, p. 37). In this context, gender and indigeneity intersect significantly, as Indigenous women experience compounded marginalization due to both their ethnic identity and gender. State-led development projects and land policies frequently overlook the traditional land rights of indigenous communities, resulting in displacement and loss of livelihoods.

Navigating land use in the CHT

The land tenure system among the hill people became closely linked to lease agreements for plough and jum cultivation (a kind of traditional shifting cultivation). Contemporary land management issues arose with the introduction of plough cultivation, which replaced traditional jum practices. The colonial government ignored the Indigenous system and forced the hill people to adopt plough cultivation in an effort to increase revenue collection. This shift in cultivation patterns diminished traditional land ownership and restricted the hill people's control over their land. The lease system formalized the rights of lessees, or hill people, to small leased areas, while unleashed areas remained available for others to claim. This documentation of leased land served as proof of ownership for the hill people, overshadowing their traditional ownership rights. These colonial reforms in land management and tenure have resulted in a long-standing crisis regarding land ownership and the relationships between Indigenous and Bengali settler communities in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) today.

According to Hunter et al. (1876), land tenure in the CHT exists only “where the British authorities have succeeded in inducing them to abandon the indigenous system of cultivation” (p. 77). There was a lack of consistent land tenure among the hill people, as they cleared jungles each year for jum cultivation and often abandoned the land from the previous year. When the hill people entered into leases for plough cultivation, they formalized their land tenure but subsequently lost control of areas they had previously cultivated as jum. The inhabitants of the CHT generally resisted the shift from jum to plough cultivation. Attempts to introduce plough cultivation often failed because the hill people preferred lighter work and valued their freedom, largely maintaining their ancestral practices of cattle rearing and herding. Despite this resistance, the colonial government was adamant about implementing plough cultivation. A report by the Deputy Commissioner of Chittagong in 1871 noted that “in consequence of the introduction of the Forest Conservancy Rules into the District, juming operations were hampered and circumscribed” (Hunter et al., 1876, p. 78). Capt. Lewin (1869) expected that the introduction of forest conservancy restrictions would compel the hill people to shift from jum to plough cultivation (Lewin, 1869, p. 14).

However, J.P. Mills, a British Indian Civil Servant and Advisor to the Governor for Tribal Areas and States, later claimed in 1926 that there was insufficient flat land suitable for plough cultivation in the CHT. He observed that the British government had not properly considered jum cultivation or given it the attention it deserved. The distribution of land for plough cultivation disrupted traditional land management practices. The British government allocated land among the CHT people and imposed restrictions on cultivation patterns. According to Hunter et al. (1876, p. 78), some hill people accepted the land management system for plough cultivation, motivated by dissatisfaction with their tribal chief and the restrictions on their jum operations. Some hill people applied for land leases to establish villages and practice plough cultivation, often receiving favorable terms. Notably, the government offered 3 Rupees for each family in advance, to be repaid over five years at an annual interest rate of 5 percent. Later, Hutchinson (1909, p. 94) stated that the rent for leased land designated for plough cultivation was intentionally kept low to encourage its adoption.

Conclusion and Discussion

Discussion

The evolution of knowledge production by the state in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) of Bangladesh is closely linked to colonial and post-colonial governance. Initially, British colonial policies focused on resource extraction and control, which marginalized Indigenous knowledge systems and practices. After independence, the Bangladeshi state continued this trend, often prioritizing national economic interests over local needs. Michel Foucault's ideas about power, resistance, and the role of discourse provide a useful framework for analyzing and challenging dominant narratives. These concepts advocate for marginalized groups and promote social change among various socially vulnerable populations. Discourse plays a crucial role in creating knowledge, particularly in how the state and ethnic majorities have constructed narratives about Indigenous communities in the CHT during both colonial and post-colonial periods. Control over knowledge production is inherently linked to power dynamics, where power creates knowledge, and knowledge reinforces power (Foucault, 1980). Those in authority, such as government officials and external experts, often dominate the narrative, sidelining ethnic knowledge and practices. This leads to the production of knowledge that ignores existing local perspectives, ultimately affecting the legitimacy of policy implementation.

To reimagine identity, gender, and land among ethnic minorities in the CHT and foster more inclusive and sustainable solutions, we can focus on the following key areas: Existing Knowledge Systems (EKS) can offer valuable alternatives to dominant development paradigms by emphasizing the significance of local ecologies and historical contexts. Transforming EKS within these domains can pave the way for sustainable and equitable development (Banerjee, 2021). This perspective aligns with the situation in the CHT, where the marginalization of ethnic minorities arises from colonial and post-colonial policies that have overlooked Indigenous knowledge and practices. Political dynamics that shape environmental issues in developing countries and unequal power relations contribute to a politicized environment, where both material and discursive struggles over resources are influenced by broader political and economic forces. Bryant’s work emphasizes the importance of understanding these power dynamics to effectively address the environmental degradation and social inequalities faced by local communities (Bryant, 1998). Colonial and post-colonial policies have systematically marginalized ethnic minorities in the CHT region. Escobar examines development policies that have served as mechanisms of control, influencing the thoughts and actions of the affected countries. He explores how development discourse has shaped the social and economic realities of nations labeled as “Third World” after World War II, highlighting the integration of Western economic practices into the development strategies imposed on these countries (Escobar, 1988). Colonial administrations frequently imposed boundaries and classifications that continue to influence contemporary ethno-territorial arrangements in the CHT. The concepts of 'governmentality' and 'counter-conducts' can analyze how ethnic struggles can both challenge and reinforce dominant ethno-territorial regimes. Anthias and Hoffmann illustrate their points with six ethnographic case studies from Argentina, Bolivia, Cambodia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Paraguay, and Peru (Anthias and Hoffmann, 2021). It is crucial to acknowledge and incorporate diverse ontologies, especially those of Indigenous peoples, into environmental governance in the CHT. Recognizing the right to self-determination, as stated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), and validating Indigenous ontologies as legitimate governance systems. DePuy et al. (2021) propose that embracing ontological pluralism can help address the colonial legacies found in current governance practices and promote both material and cognitive justice.

Community-based decision-making processes can empower CHT individuals to become “environmental subjects” who actively care for and manage their environment. Agrawal (2005) explores how rural residents in Kumaon, India, developed a sense of environmental stewardship through community-based forest management, highlighting the effectiveness of local involvement in fostering environmental responsibility. The concepts of ‘border thinking’ and ‘border epistemologies’ advocate for alternative ways of knowing and being that resist the homogenizing forces of global modernity. These ideas propose a more pluralistic and inclusive understanding of knowledge that values local and Indigenous perspectives in the CHT. Such epistemologies emerge from the experiences and viewpoints of marginalized communities in Latin America, ensuring inclusive and diverse understandings of Indigenous knowledge (Escobar, 2007).

It is important to appreciate diverse cultural contexts and advocate for a nuanced and respectful engagement with marginalized groups, recognizing their unique histories and practices. The imposition of external values and policies can marginalize local communities, especially women, and lead to cultural imperialism. Lughod (2002) criticized the simplistic and patronizing view that Muslim women need to be rescued from their own cultures, particularly in the context of the War on Terror in Afghanistan. In reimagining CHT, we should consider implementing interdisciplinary approaches to effectively address environmental challenges. By integrating various fields of study, we can develop comprehensive strategies that are more robust and adaptable to complex ecological issues. Additionally, discussing how anthropological perspectives in political ecology reveal the power dynamics and inequalities that shape environmental outcomes would be beneficial. As Karlsson (2015) highlights, these perspectives can uncover the underlying social and political factors that influence environmental policies and practices, leading to more equitable and sustainable solutions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, reimagining ethnic marginalization in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) through the lenses of identity, gender, and land use requires a profound shift in how knowledge is produced and valued. The historical context of colonial and post-colonial governance has deeply influenced the marginalization of Indigenous knowledge systems and practices. By embracing Foucault’s concepts of power, resistance, and discourse, we can challenge dominant narratives and advocate for the inclusion of marginalized voices. The control over knowledge production has historically been linked to power dynamics, where those in authority have often sidelined ethnic knowledge and practices. Recognizing and integrating Already Existing Knowledge Systems (AEKS) can provide valuable alternatives to dominant development paradigms, emphasizing the importance of local ecologies and historical contexts. This approach aligns with the need for sustainable and equitable development in CHT. Understanding the political dynamics and unequal power relations that shape environmental issues is crucial for addressing the social inequalities experienced by local communities. The colonial and post-colonial policies that have systematically marginalized ethnic minorities must be critically examined and reformed. Embracing diverse ontologies and validating Indigenous governance systems, as proposed by DePuy et al., can address colonial legacies and promote both material and cognitive justice. Community-based decision-making processes can empower individuals in the CHT to become active stewards of their environment, fostering a sense of ownership and responsibility. Concepts like “border thinking” and “border epistemologies” advocate for a more pluralistic and inclusive understanding of knowledge, valuing local and Indigenous perspectives.

Ultimately, appreciating diverse cultural contexts and engaging respectfully with marginalized groups is essential. This approach not only recognizes their unique histories and practices but also challenges the imposition of external values and policies that can lead to cultural imperialism. By reimagining ethnic marginalization through these lenses, we can work towards a more just and inclusive future for marginalized communities.

References:

Abu-Lughod, Lila (2002). Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving? Anthropological Reflections on Cultural Relativism and Its Others. American Anthropologist, 104 (3): 783-790.

Agrawal, A. (2005). Environmentality: Community, intimate government, and the making of environmental subjects in Kumaon, India. Current Anthropology, 46(2), 161-190.

Ahammad, R., & Stacey, N. (2016). Forest and agrarian change in the Chittagong Hill Tracts region of Bangladesh. Agrarian change in tropical landscapes, 190-233.

Anthias, P., & Hoffmann, K. (2021). The making of ethnic territories: Governmentality and counter-conducts. Geoforum, 119, 218-226.

Ashrafuzzaman, M. (2014). The tragedy of the Chittagong Hill Tracts in Bangladesh: Land rights of indigenous people. Thesis, Lund University.

Banerjee, M. (2021). The politics of knowledge in development: An analytical frame. Studies in Indian Politics, 9(1), 78-90.

Bhandar, B. (2018). Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership. Durham: Duke University Press,

Blomley, N. (2023). Territory: The New Trajectories in Law. Routledge.

Bryant, Raimond L (1998). Power, knowledge and political ecology in the Third World. Progress in the Physical Geography. 22(1): 79-84

Chakma, B. (2010). The post-colonial state and minorities: Ethnocide in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. Commonwealth & Comparative olitics, 48(3), 281-300.

Coulthard, G. S. (2014) Red skin, white masks: Rejecting the colonial politics of recognition. Minneapolis: Minnesota.

D’ Costa, B. (2014). Marginalisation and Impunity: Violence against Women and Girls in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Chittagong Hill Tracts Commission, International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, and Bangladesh Indigenous Women's Network.

DePuy, W., Weger, J., Foster, K., Bonanno, A. M., Kumar, S., Lear, K., Basilio, R., & German, L. (2021). Environmental governance: Broadening ontological spaces for a more livable world. EPE: Nature and Space, 0(0), 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/251484862110185651

Elmhirst, R. (2015). Feminist political ecology. In T. B. Perreault, Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology, pp. 519-530. Oxon, New York: Routledge.

Escobar, A. (1984) Discourse and power in development: Michel Foucault and the relevance of his work to the Third World. Alternatives 10: 377-400.

Escobar, A. (2007) Worlds and knowledge otherwise. Cultural Studies, 21:2-3, 179-210, https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162506

Fairhead, J., Leach, M., & Scoones, I. (2014). Green grabbing: a new appropriation of nature? Journal of Peasant Studies, 39:2, 237-261.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977.

Foucault, M. (2006), Governmentality. In: A. Sharma and A. Gupta (Eds), Anthropology of the State: A Reader. Blackwell.

Ghosh, R., Abdi, A. A., & Ayaz Naseem, M. (2008). "Identity in Colonial and Postcolonial Contexts: Select Discussions and Analyses". In EDITORS? (Eds), Decolonizing Democratic Education, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789087906009_007

Giovarelli, R., & Wamalwa, B. (2011). Land Tenure, Property Rights, And Gender. USAID.

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.

Harding, S. (1991). Whose Science? Whose Knowledge? Thinking from Women’s Lives.

Hunt, E.M. The Past, Present, and Future States of Political Theory. Soc 59, 119–128 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-022-00703-1

Hunter, W.W.; Mackie, A.W.; O’Donnell, C.J. 1876. A Statistical Account of Bengal, Volume VI (Chittagong Hill Tracts, Chittagong, Noakhali, Tipperah, Hill Tipperah. London, Trubner & Co.

Hutchinson, R.H.S.1909. Eastern Bengal and Assam District Gazetteer: Chittagong Hill Tracts. Allahabad, Pioneer Press.

Jasanoff, S. (2004). States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and Social Order.

Jasanoff, S. (2011). The politics of public reason. In P. Baert & F. Domínguez Rubio (Eds.), The politics of knowledge (pp. 11-32). Routledge.

Karlsson, B. G. (2015). Political ecology: Anthropological perspectives. In: Wright, James, D. International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavorial Sciences, pp. 350-355. Vol: 18 Oxford: Elsevier.

Latour, B. (1987). Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers Through Society.

Levene, M. (1999). The Chittagong Hill Tracts: A case study in the political economy of creeping genocide. Third World Quarterly, 20(2), 339-369.

Lewin, C. T. H. 1869. The Hill Tracts of Chittagong and the Dwellers Therein; With Comparative Vocabularies of the Hill Dialects. Calcutta, Bengal Printing Company, Limited.

Mohsin, A. (1997). The Politics of Nationalism: The Case of the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh. The University Press Limited, Dhaka.

Mohsin, A. (2003). The Chittagong hill tracts, Bangladesh: On the difficult road to peace. International Peace Academy Occasional Paper Series. Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc. Colorado.

Moore, A., Invernizzi-Accetti, C., Markovits, E., Pamuk, Z., & Rosenfeld, S. (2020). Beyond populism and technocracy: The challenges and limits of democratic epistemology. Contemporary Political Theory, 19(4), 730-752. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41296-020-00398-1

Rahman, M. (2011). Struggling Against Exclusion: Adibasi in Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. [Doctoral Thesis (compilation), Sociology]. Lund University.

Reddy, G., & Gleibs, I. H. (2019). The endurance and contestations of colonial constructions of race among Malaysians and Singaporeans. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 408784.

Rozaria, S.T. (2016). Activists demand end to indigenous discrimination. UCA News. 12 August. Available at Activists demand end to indigenous discrimination - UCA News

Said, Edward W. (1978). Orientalism. New York: Random House. [Introduction]

Santos, B. de S. (2014). Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide.

Sato, C. (2019). Toward a postcapitalist feminist political ecology’s approach to the commons and commoning. International Journal of the Commons, 13(1), 36-61.

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the Subaltern Speak? In Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples.

theoryofknowledge.net. (2024, February 19). Knowledge and politics - theoryofknowledge.net. https://theoryofknowledge.net/free-tok-notes/tok-optional-themes/knowledge-and-politics/#:~:text=Knowledge%20%26%20politics%3A%20a%20quick%20overview%20The%20optional,dissemination%2C%20and%20manipulation%20of%20knowledge%2C%20and%20vice%20versa.

Tuana, N. (2006). The Speculum of Ignorance: The Women’s Health Movement and Epistemologies of Ignorance.

Uddin, N. (2012). Politics of cultural difference: Identity and marginality in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh. South Asian Survey. 17. 283-294.

Annex 1: Map of Bangladesh, with CHT in green

Just read this! Surely a masterpiece on understanding ethnic marginalization through the politics of knowledge.