OAJ Hot Take: Doing Brandeis Justice

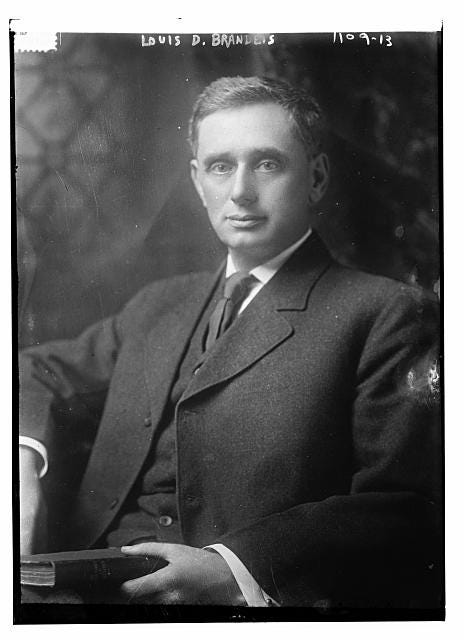

For one of the most important policy thinkers of American history, we sure don’t talk about Louis Brandeis much at the university bearing his name.

Do you have thoughts about OAJ's Hot Takes or other pieces published in the Open Air Journal? Share a letter to the editor at openair@brandeis.edu. We are committed to publishing letters that contribute to constructive dialogue among the Heller community. Also, consider submitting to our Spring 2023 Issue: People Power (submission period February 17th to March 17th).

I am only four months away from graduating with a master’s degree in public policy from the university named after Louis Brandeis: the people’s lawyer, Supreme Court Justice, and prolific policy thinker. It’s apparent that we’re taking part in the legacy of an intellectual giant at Heller. There’s one problem though –– I never learned anything about him here. By graduation day, I’ll have spent about 624 classroom hours studying policy at the Heller School with barely a mention of Justice Brandeis.

Most seem to know some basic facts about him: he was the first Jewish Supreme Court Justice and he was an early progressive thinker. Many also know he was instrumental in building American support for the creation of a Jewish state within Palestine as the leader of the American Zionist movement.

Others may know him for the “Brandeis brief,” the practice of using empirical evidence from social sciences to inform legal decisions. It seems obvious that the Supreme Court should consider the real world impact of their decisions, but that wasn’t really done until Brandeis. Thurgood Marshall and Ruth Bader Ginsberg used Brandeis briefs to strengthen legal arguments for race and gender equality. Even still, or perhaps because of the use of Brandeis briefs to tie decisions to reality, the current conservative court views the use of sociology in law with contempt.

Brandeis believed in the common citizen. He supported unions, wage and hour laws, and the ability for people to govern themselves. This final point led him to be heavily critical of the domination of large businesses, famously taking big banks to task in Other People’s Money. Even today, corporate economists (often disparagingly) call anti-monopolists “neo-Brandeisians.”

Brandeis was also suspicious of federal power. He considered himself an inheritor of Jefferson’s intellectual tradition, with the same deference to small farmers and producers. He believed that one of the best protections against tyranny was for citizens to develop their own faculties through small enterprises and leisure time.

His Jeffersonian inclinations are also apparent in his love of states, which he referred to as “laboratories of democracy.” There was no bigger federalism fan until Mike Doonan emerged on the scene.

His civil libertarian bona fides are certainly apparent in his defenses of free speech and privacy. In what became known as the “counterspeech doctrine” Brandeis articulated a deeply American approach to freedom of expression: he asserted the best response to false and hateful speech is true and righteous speech, not censoring of the bad speech. He also foresaw the danger of emerging communications technologies, such as the telephone, to privacy, proclaiming that it was everyone’s fundamental right “to be left alone.” Imagine what he would have to say about the National Security Agency’s surveillance program!

Current events show the consistent relevance of Brandeis’ contributions as a legal and policy thinker. It’s a given that he’d be on the side of Swifties in their crusade against Ticketmaster and a proponent of antitrust enforcement against tech giants like Google. He’d also likely be a fan of Lina Khan, the head of the Federal Trade Commission, for the audacious banning of noncompete agreements, which have depressed workers’ wages and ability to easily change jobs.

However, this is not to say that Brandeis’ corpus and impact should be viewed uncritically. He was ambivalent at best to issues of racial equality despite being an advocate for other social movements like the labor movement and women’s suffrage. Like many progressive thinkers of his day, he was a member of groups supportive of eugenics and ruled with the majority in a case allowing forced sterilization.

The impact of his preferred policies are also not playing out as cleanly as he has them on paper. The salutary potential of states as laboratories of democracy seems like a distant memory from a progressive perspective as Republican-controlled states rig electoral maps, ban books, and restrict reproductive liberty. Even the absolutist American conception of free speech may need updating in the era of social media where disinformation and misinformation spread like wildfire.

America’s relationship with Israel, built in part by Brandeis’ early advocacy prior to its official founding, also deserves reevaluation. As a person with a strong (albeit flawed) sense of justice, how would he feel about Israel committing the crime of apartheid against Palestinians, its hard-right turn, and the United States shielding the state from accountability?

All this is to say, exploring the ideas and life of Louis Brandeis is an edifying way to understand the past, present, and future of the United States. We should really know more about him and his ideas at Heller, particularly in the MPP program.

Spending time on Brandeis would come at the expense of cutting or shortening the coverage of something else perhaps equally or more important. With limited time in our two year program, it’s certainly challenging to add in all the things we want and need. The namesake of the university should at least get a seminar though.

Connect with this creator: